This is my third post about the Milky Way, the galaxy that contains our Solar System. The descriptor “milky” is derived from the galaxy’s appearance from Earth: a band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars that cannot be individually distinguished by the naked eye. On this occasion, I was accompanied by Harv Emter, friend, photographer and fellow member of the Canmore Camera Club.

As I continue to photograph the Milky Way, I’ve learned more about the technique and hopefully I’m getting better at it. There are several challenges unique to astrophotography, particularly with shooting the Milky Way.

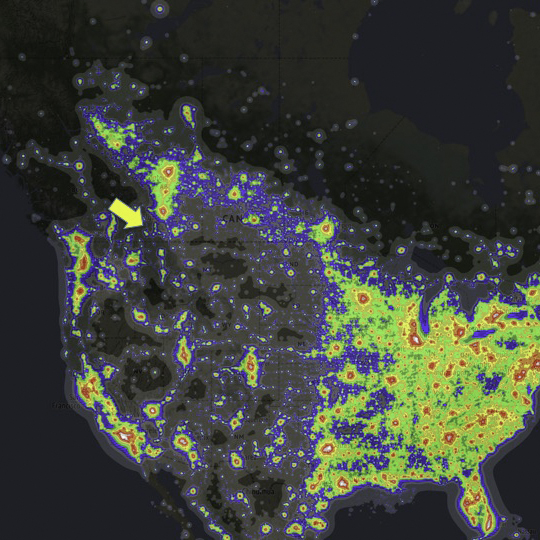

Most importantly, it’s necessary to have clear skies with the least ambient light possible. That excludes moonlit nights and proximity to any population centres, sources of “light pollution”. The best time of the month is the New Moon, when the moon is entirely shaded (and a couple of days before and after, when the crescent moon is reflecting very little sunlight). Our destination for this shoot was the Chain Lakes Provincial Park, in the southwest corner of Alberta, distant from strong sources of light. It is surprisingly difficult to find such places. This map of our continent is overlaid with the intensity of light at nighttime (the hotter the colour, the greater the light intensity). As is very apparent, North America is very brightly lit, particularly on the eastern seaboard of the United States. Our shooting location (yellow arrow) was just south of the agglomeration of light in the Edmonton to Calgary corridor.

Once we’ve found a suitable area, we are able to determine, where in the sky the Milky Way will appear and when, using an iPhone app. It’s a great planning tool that helps us to select precisely where we’ll take the shots.

The actual photographing has its challenges as well. By choice, the locations are very dark, making it difficult even to see what you’re doing. Flashlights and headlamps are essential. The autofocus on the camera doesn’t work in the dark! The solutions are to focus manually on a source of bright light (a star, for example) or set the focus in daylight, before venturing out at night.

There is very little light to even capture. The camera must be wide open to receive the small amount of light available. That means a large aperture selection, high sensor sensitivity and a long exposure. The earth’s rotation causes the stars to move in relation to the stationary camera. Consequently, exposures are limited to ~20 sec. to avoid stars becoming streaks rather than points of light. Long exposures cause the camera’s sensor to heat up, creating electronic noise which appears in the form of coloured pixels and speckles on the image. There are many different ways to address noise including “in camera” noise reduction settings and software solutions that can be applied in developing the image.

It’s important to keep in mind that for any photograph you want good composition. We scout our locations in advance to ensure we have the landscape available to create an interesting picture. In the example that follows (Night Sky Across Chain Lake), there is the water and the reflections it contributes to the image. In the bottom right, in the shadows is a boat launching ramp. In a photo like this, I want lots of sky and I want some interesting foreground as well. The Milky Way is very “tall” at this time of the year, almost vertical in the sky. To do it justice a tall photograph is warranted. This particular photograph is a 3-row, vertical panorama, three separate photographs stitched together vertically to create a photograph that includes a substantial portion of the galaxy above the horizon.

Peter

Those pics are Phenomenal

Thank you.

Nice!!!

Excellent Peter! I am still dreaming of taking pictures of the Milky Way like yours.

Wonderful pictures Peter! Such great photography.

Brenda

Fantastic!!!!! with a beautiful reflection :):)

Thanks Peter

Helen

Hi peter:

I can look and look at your pictures, they are so awesome and have me wishing…one day.

Hi to Rolande